I recently stumbled upon this nice blog post by Josh Barczak,

comparing the performance of various C++ string tokenisation routines. The crux of it is that by writing low-level

C-like code, Josh was able to get better performance than by using Boost or either of the standard

library solutions he tried.

This post is meant as a rebuttal, showing that by using the STL properly we can get simple, elegant, generic,

reusable code that still performs better than the hand-coded solution.

The problem

So let’s take look at the problem. In his code,

Josh takes a reasonably large (~20MB) text file, splits it up into tokens, and then copies those

tokens to an output file. The final hand-coded method looks like this:

static bool IsDelim( char tst )

{

const char* DELIMS = " \n\t\r\f";

do // Delimiter string cannot be empty, so don't check for it

{

if( tst == *DELIMS )

return true;

++DELIMS;

} while( *DELIMS );

return false;

}

void DoJoshsWay( std::ofstream& cout, std::string& str)

{

char* pMutableString = (char*) malloc( str.size()+1 );

strcpy( pMutableString, str.c_str() );

char* p = pMutableString;

// skip leading delimiters

while( *p && IsDelim(*p) )

++p;

while( *p )

{

// note start of token

char* pTok = p;

do// skip non-delimiters

{

++p;

} while( !IsDelim(*p) && *p );

// clobber trailing delimiter with null

*p = 0;

cout << pTok; // send the token

do // skip null, and any subsequent trailing delimiters

{

++p;

} while( *p && IsDelim(*p) );

}

free(pMutableString);

}

Now I don’t want to pick on Josh, because this code works, and it’s faster than anything else he tried.

But… well, let’s just say it’s not a style of code I would enjoy working with. Let’s see how we can come up

with something better.

Evolving a splitting algorithm

First, let’s take a step back and look at things from a mile-high view: given an input string str and

a set of delimiters delim, how would you describe to someone in plain English how to split the string?

Bear in mind that although it’s not required in this case, for other uses we we may want to keep empty

tokens which occur when we have two consecutive delimiters.

It turns out this isn’t so easy. My effort is the following:

“If the string is empty, then you’re done. Otherwise, take the first character of str, and call it first.

If first is a delimiter, then the string begins with an empty token; save the token, remove first from the

string and start again. If first is not a delimiter, then scan along the string from first until you find

another character which is a delimiter, or else reach the end of the string. Now the interval [first, last)

consists of one token; save that token. Remove the closed interval [first, last] from the string

and restart.”

Translating this naively into C++, we get something this:

// Version 1

bool is_delimiter(char value, const string& delims)

{

for (auto d : delims) {

if (d == value) return true;

}

return false;

}

vector<string>

split(string str, string delims)

{

vector<string> output;

while (str.size() > 0) {

if (is_delimiter(str[0], delims)) {

output.push_back("");

str = str.substr(1);

} else {

int i = 1;

while (i < str.size() &&

!is_delimiter(str[i], delims)) {

i++;

}

output.emplace_back(str.begin(), str.begin() + i);

if (i + 1 < str.size()) {

str = str.substr(i + 1);

} else {

str = "";

}

}

}

return output;

}

This algorithm actually works, provided you’ve got enough patience – with all the string copies going on,

it’s very, very slow. (Though if you use std::experimental::string_view, which doesn’t copy but just

updates a couple of pointers, then this actually performs respectably – but we can still do better.)

Now this isn’t great, but it’s at least something to start with. Let’s iterate on it and see where we get.

The first thing we want to do is to stop making all the string copies. That’s actually not too difficult.

Instead of chopping the front off the string every time we go through the loop, we’ll use a variable to keep

track of the “start”. Having done that, and with a minor tidy-up, we arrive at:

// Version 2

bool is_delimiter(char value, const string& delims)

{

for (auto d : delims) {

if (d == value) return true;

}

return false;

}

vector<string>

split(const string& str, const string& delims)

{

vector<string> output;

int first = 0;

while (str.size() - first > 0) {

if (is_delimiter(str[first], delims)) {

output.push_back("");

++first;

} else {

int second = first + 1;

while (second < str.size() &&

!is_delimiter(str[second], delims)) {

++second;

}

output.emplace_back(str.begin() + first, str.begin() + second);

if (second == str.size()) {

break;

}

first = second + 1;

}

}

return output;

}

Again, this works, and it’s much faster than before. But… well, it’s ugly. We have two different cases

depending on whether str[first] is a delimiter or not, and we’re calling is_delimiter() twice in

many cases. Can we collapse these cases down to a single one?

It turns out we can, with just a minor change: instead of defining second to start at first + 1, we just

initialize it with first instead. Now, if first is a delimiter then the inner while loop will exit

immediately and second will never be incremented, so we end up emplacing an empty string in the vector

just as we’d like. Once we collapse down the two cases, we end up with version 3 of our algorithm:

// Version 3

bool is_delimiter(char value, const string& delims)

{

for (auto d : delims) {

if (d == value) return true;

}

return false;

}

vector<string>

split(const string& str, const string& delims)

{

vector<string> output;

int first = 0;

while (first < str.size()) {

int second = first;

while (second < str.size() &&

!is_delimiter(str[second], delims)) {

++second;

}

output.emplace_back(str.begin() + first, str.begin() + second);

if (second == str.size()) {

break;

}

first = second + 1;

}

return output;

}

We’ve only removed 4 lines, but this is already beginning to look much better.

Enter the iterator

Up until now, you’ll notice that we haven’t used iterators, but rather first and second have been

integer indices into the string. That was deliberate, because a lot of people seem to be put off by

iterators. They needn’t be: an iterator is really just an index into some set. All we need to do is to

change first = 0 to first = std::cbegin(str), and the str.size() checks into checks against

std::cend(str):

// Version 4

bool is_delimiter(char value, const string& delims)

{

for (auto d : delims) {

if (d == value) return true;

}

return false;

}

vector<string>

split(const string& str, const string& delims)

{

vector<string> output;

auto first = cbegin(str);

while (first != cend(str)) {

auto second = first;

while (second != cend(str) &&

!is_delimiter(*second, delims)) {

++second;

}

output.emplace_back(first, second);

if (second == cend(str)) {

break;

}

first = next(second);

}

return output;

}

As you can see, the code is barely any different, and performs identically.

Now, let’s turn our attention to the inner while loop. Slightly reorganised, this is:

auto second = first;

while (second != cend(str) {

if (is_delimiter(*second, delims)) {

return second;

}

++second;

}

What is this snippet really doing? It’s saying “find the first element in the interval [first, end()) which

is a delimiter”. Now, “is a delimiter” means “is a member of the set of delimiters”, so if we put these

together then the while loop is saying

“Find the first element of the interval [first, end()) which is also in the interval

[delims.begin(), delims.end())”

Fortunately for us, there is a stardard algorithm that does exactly this: it’s called

std::find_first_of(). Let’s update our

code to use this algorithm, which gives us the (almost) final version:

// Version 5

vector<string>

split(const string& str, const string& delims)

{

vector<string> output;

auto first = cbegin(str);

while (first != cend(str)) {

const auto second = find_first_of(first, cend(str),

cbegin(delims), cend(delims));

output.emplace_back(first, second);

if (second == cend(str)) break;

first = next(second);

}

return output;

}

This version still adds empty strings to the output when it comes across two consecutive delimiters. This

is sometimes what people want, but sometimes not, so let’s make it an option. Also, the most common case

for splitting is to use a single space as a delimiter, so we’ll use that as a default parameter. Making

these changes, and putting back the std:: directives that we have so far elided, we our final string

splitter:

// Final version

std::vector<std::string>

split(const std::string& str, const std::string& delims = " ",

bool skip_empty = true)

{

std::vector<std::string> output;

auto first = std::cbegin(str);

while (first != std::cend(str)) {

const auto second = std::find_first_of(first, std::cend(str),

std::cbegin(delims), std::cend(delims));

if (first != second || !skip_empty) {

output.emplace_back(first, second);

}

if (second == std::cend(str)) break;

first = std::next(second);

}

return output;

}

This code is simple enough that we don’t even need to add comments. The core of it is the find_first_of()

call, which is easily looked up even if you can’t guess what it does from the name. But we can do better yet.

A more generic tokeniser

It’s long been a criticism of those coming to C++ from other languages that there is no split() function

for strings in the standard library. The reason is that doing so in a generic way is pretty tricky. Let’s

have a try at it now:

// Bad generic split

template <class Input, class Delims>

vector<Input>

split(const Input& input, const Delims& delims,

bool skip_empty = true)

{

vector<typename Input> output;

auto first = cbegin(input);

while (first != cend(input)) {

const auto second = find_first_of(first, cend(input),

cbegin(delims), cend(delims));

if (first != second || !skip_empty) {

output.emplace_back(first, second);

}

if (second == cend(input)) break;

first = next(second);

}

return output;

}

Unfortunately, this falls apart as soon as we try to call it with a string literal, because the compiler

will complain that it cannot intantiate a vector<const char[17]> (or something similar). Also, what if

we don’t want to output a vector? A generic solution should surely let us use whatever container we

like. What if we are streaming in the input via istream_iterator? How do we pass the output to

an ostream?

This problem is pretty tricky, but it’s not insurmountable. Our splitting algorithm is sound – it will

work for anything that models the InputIterator concept. The problem is, what do we do with the tokens once

we’ve found them? Actually, the answer is obvious: we should let the caller do whatever they like, by letting

them pass in a function which we will call every time we find a token.

Then our generic solution then looks like this:

// Good generic "split"

template <class InputIt, class ForwardIt, class BinOp>

void for_each_token(InputIt first, InputIt last,

ForwardIt s_first, ForwardIt s_last,

BinOp binary_op)

{

while (first != last) {

const auto pos = std::find_first_of(first, last, s_first, s_last);

binary_op(first, pos);

if (pos == last) break;

first = std::next(pos);

}

}

This simply calls the given function for each token (hence the name), passing the first and

one-past-the-end iterators we’ve found. Writing our split() for strings in terms of this generic

function is trivial:

vector<string>

split(const string& str, const string& delims = " ",

bool skip_empty = true)

{

vector<string> output;

for_each_token(cbegin(str), cend(str),

cbegin(delims), cend(delims),

[&output] (auto first, auto second) {

if (first != last || !skip_empty) {

output.emplace_back(first, second);

}

});

return output;

}

Our generic for_each_token() is simple, elegant, and it shows off very nicely

the power of the STL. All of which is very nice, but pointless if it isn’t fast. Is it fast?

Yes. Yes it is.

Performance

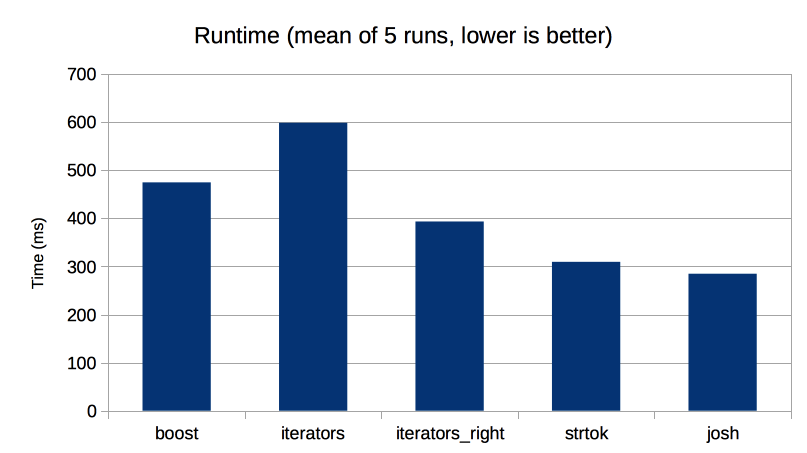

In order to measure performance, we’ll use Josh’s original microbenchmark from

here, slightly modified to use a timer

based on std::chrono::high_performance_clock rather than boost::timer. Re-running the original

tests on my system (GCC 5.3 with -O3 on a Macbook Pro running OS X El Capitan), and taking the average

of 5 runs for each algorithm, I get the following profile:

As you can see, the results are almost the same as Josh’s, except that Boost does slightly better this time.

Josh’s approach is still fastest, with strtok() a close second.

Now let’s add our method, using the generic algorithm above. This is the code I added:

// 5 statements

template <class InputIt, class ForwardIt, class BinOp>

void for_each_token(InputIt first, InputIt last,

ForwardIt s_first, ForwardIt s_last,

BinOp binary_op)

{

while (first != last) {

const auto pos = find_first_of(first, last, s_first, s_last);

binary_op(first, pos);

if (pos == last) break;

first = next(pos);

}

}

// 2 statements

void DoTristansWay(std::ofstream& cout, std::string str)

{

constexpr char delims[] = " \n\t\r\f";

for_each_token(cbegin(str), cend(str),

cbegin(delims), cend(delims),

[&cout] (auto first, auto second) {

if (first != second)

cout << string(first, second);

});

}

The full code is available in this gist.

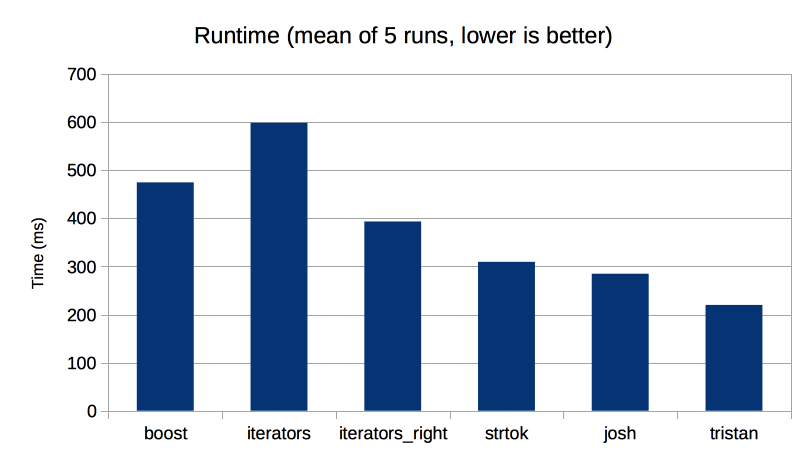

This time, the results look like this:

As you can see, our algorithm is by far the fastest of all the options. The average runtime

for the generic algorithm on my system is 220ms, against 285ms for the next best – that’s a

1.3x speed-up.

Not only that, but we’ve done it with just seven statements (using the metric from the original

post), as opposed to 21 for the low-level version. 1.3x the performance with 1/3rd of the code?

I’ll take that any day of the week. That’s the power of the STL.

Discussion

In the original post, Josh presents the “conventional wisdom” as being the following:

You shouldn’t roll your own code. The standard library was written by gurus and mere

mortals won’t do better. Even if you do, you’ll write bugs, and you’ll end up spending

more time fixing them than it’s worth.

This is all true, but I would put it slightly differently: I would say that if a standard library

tool exists, then use it, but make sure you pick the right tool for the job.

In this case, despite the prevalence of suggestions on the internet, std::stringstream is

the wrong tool to use for string splitting. The right tool is std::find_first_of.

Once we use that, then not only do we get simple code, but it turns out to be much faster too.

The beauty of the STL is that it provides composable, low-level algorithms from which you

can build up complex behavior. Sean Parent makes this argument far better than me; in his

fantastic C++ Seasoning talk

at Going Native 2013, he shows how you can use the STL algorithms in places where it’s not

obvious. The video is very highly recommended.

Sean advocates that every C++ programmer should share at least one useful algorithm publicly per year.

Hopefully I’ve now met my quota for 2016.